This post is a reflection on being part of making a maturing infrastructure organization for nearly five years.

When I joined Production Engineering at Shopify, it was barely 30 people. We went for a team dinner around that time and I remember how my manager paid for it with his credit card because points. Now we are at >200 people, and at the last pre-pandemic offsite we had a huge ballroom booked for the dinner. Clearly it wasn't billed to an individual's credit card.

Through my there years there, I've seen how we've solved scalability and growth by introducing boundaries and new levels of abstraction.

Now that I'm noticing this pattern at other companies too, I believe that managing layers of abstraction is the key tool to solving scalability problems.

The story of scaling Redis

As the most of other Ruby on Rails shops, we've been running job queues on Redis with the Resque gem (you might have also worked with Sidekiq which is Resque's successor). Both of those libraries are built on top of Redis, a key-value database written in C that also provides primitives like List and Hash. As a database, Redis keeps those lists/queues in memory for you, and dumps them to the disk every once in a while if you have persistence enabled.

The way how Resque (or Sidekiq) API is designed, you can grab Redis client by calling Resque.redis and query that Redis directly for any other operations. This is convenient, and having hundreds of developers at Shopify at that point, it was easy for everyone to start dumping non-jobs data to Redis, thanks to the ease of access to Resque.redis in the Rails app.

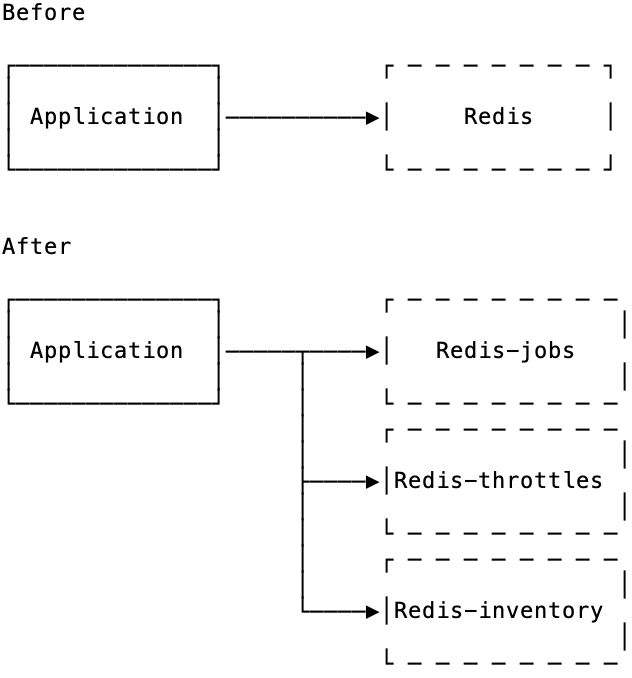

The side effect of this easy-to-use API was that Redis became overloaded not only by the throughput of background jobs, but also by all arbitrary features where people have plugged Resque.redis to store ephemeral keys like throttles or inventory data.

Lesson #1: easy to access APIs can get harmful, especially when it's designed for a smaller scale and misused at a larger scale.

We introduced separate Redis instances for all non-jobs features, and for a while Resque.redis was only used for jobs.

But because Resque.redis didn't go away as a public API (even though its use was verbally discouraged), a new pile of features have developed that were writing to Resque.redis, mostly because that was a developer habit.

It took us significant amount of efforts to completely remove Resque.redis as a public accessor (see shitlist driven development) and move to not exposing Redis clients directly anywhere. Instead of giving Redis access directly, we provide a few Ruby classes that wrap Redis access, like ActiveJob, Throttle or DisposableCounter.

Lesson #2: it's going to be much easier to scale a data store when the subset of operations is limited and its clients are not exposed directly to developers.

Proxies and connection

It's important to say that Redis is single-threaded, which means that it doesn't employ more than a single CPU. Its authors recommend scaling by introducing more Redis instances running on other CPUs and making your app somehow shard the data across multiple Redis instances - or by using Redis Cluster.

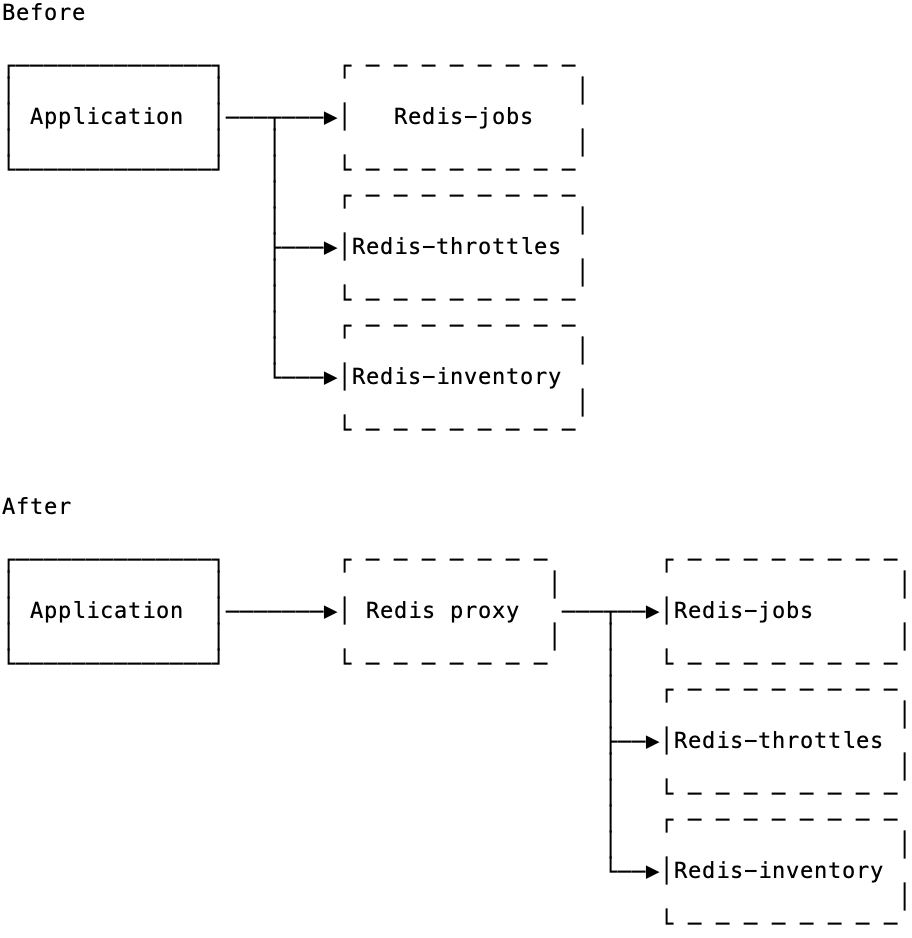

Also, the more client connections are open to Redis, the busier will be that single CPU. We started to notice that connection limits and CPU load were coming to be the two biggest bottlenecks in keeping the platform up.

As we did for the rest of stores like MySQL and memcached, we went with introducing a TCP proxy in front of Redis that would multiplex client <-> backend connections and reduce the pressure on Redis' CPU. It's incredible how much room you can buy for scalability by putting a proxy in front of Redis/MySQL/memcached.

Proxies and scalability

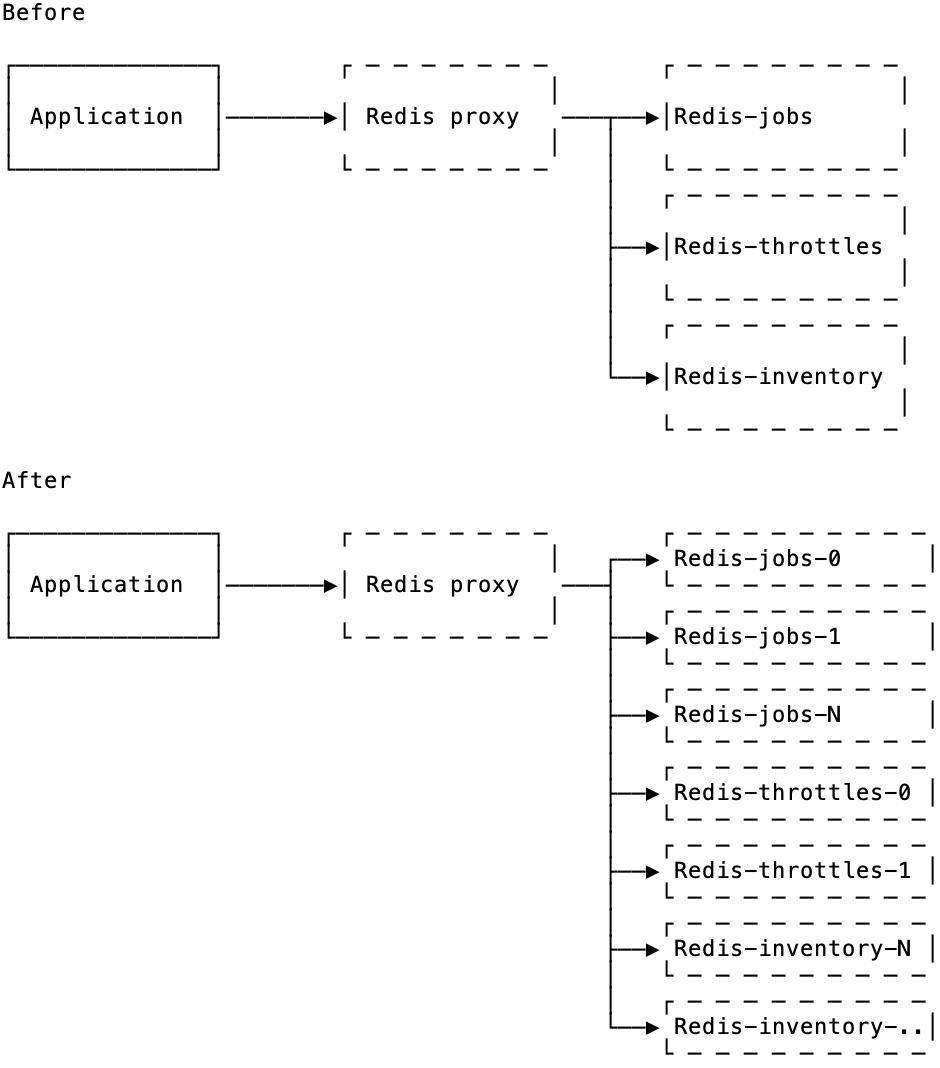

Now all operations to Redis went through a proxy and every feature like jobs or throttles had its own Redis. But every Redis was still single-threaded, and once we had extra load on jobs or on throttles, that Redis would max out on CPU and some operations would get queued and time out. We had to horizontally scale Redis for each feature.

The beauty of having a proxy in front of a database is that you now you can make changes to the backend without having to change clients. Thanks to Envoy proxy, we've been able to swap a single Redis behind the proxy with a pool of multiple Redis instances, and partitioning operations by a key.

Layers of abstraction

We've had no abstractions at first and developers used to call the Redis client directly for any operations. We went away from giving the Redis client to providing primitives that work with Redis underneath.

Later we moved away from making the application connect to Redis directly to giving them something that looks like Redis, but is actually a proxy that forwards commands to multiple Redis instances managed by infrastructure teams. That abstraction will also allow us to swap those backends on the proxy with another database like KeyDB in we wanted to.

These two steps have abstracted Redis access from the application code and decoupled code from the infrastructure, which was the key to making something scale for both the load and the number of developers.

You can see the similar pattern with Vitess, which makes the client believe that it's speaking to MySQL while it's actually speaking to a Go service that applies certain logic and forwards those MySQL queries elsewhere. Used by YouTube, Github and Slack, Vitess is gaining its popularity as a way to horizontally scaling database access without increasing the complexity on the client.

I believe that the increasing amount of abstractions is the reasonable price to pay for scalability. It works the other way around too: if some parts of your stack are abstracted and some are not, those that are not abstracted will be the first to become a scalability bottleneck.